|

| Francis Alÿs (In collaboration with Julien Devaux and Ajmal Maiwandi) REEL-UNREEL, 2011 Single channel video projection, 19:28 min, color, sound Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London |

The Francis Alÿs film REEL-UNREEL was made for dOCUMENTA (13) and is currently on view at David Zwirner Gallery in New York. It was originally meant to be shown sooner but was delayed due to interior damage caused by Hurricane Sandy. A single channel video 19:28 minutes in length, the film is the visual documentation of young boys playing with a reel of film on the streets of Kabul, Afghanistan. An artist who chooses to focus on a social discourse within the context of his work, Alÿs walks a tightrope between third world restrictions and popular, cinematic culture that is unreachable for so many. He tends to focus in a very painstakingly precise, yet almost childlike way on the world that surrounds him. As a viewer, it is easy to almost feel as a voyeur peering into a world that not only is rarely seen, but is being shown to us in a way that we’d never imagine. Such is the case with REEL-UNREEL. The film is derived on actual events that occurred in 2001 when the Taliban confiscated and burned reels of film. What they didn’t know, according to the statement at the end of the film, is that many of the reels were bootlegged and copies had been made and secretly stored. The film focuses on the dusty brown streets of the city. His depiction of the dry arid air almost makes it possible to smell the dirt and dust as it whirls around people standing in the street, animals, and cars. First a focus is placed on children playing with a thin tire and a stick. Running alongside the tire, a youth deftly remains with the tire spinning just in front of his gait. From a tire, the game transforms into that of cat and mouse chase; two boys connected, by two reels and one filmstrip. The first boy unwinds as the other collects the film as it drags through the city streets. Clink, clink, clink, the tinny metal reel bounces and rolls over the uneven surface whirring and climbing at the pace of the boys’ stride.

All throughout the work there is an underlying layer of anxiety and sadness. Even before knowing about the Taliban and how they burned reels of film, it somehow already reeks of death. In Laura Mulvey’s “Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image“(2006) the author and theorist discusses the history of cinema and celluloid. Obviously, now soon to be part of our past if not fully already, multiple still frames shown in rapid succession, allowed for the mirage of movement when projected on a screen. However, Mulvey talks about this in relationship to the concept of death. She delves into the literal, technicality behind cinema and arrives at the suggestion that it is quite phantasmagorical in nature, the fallacy of death mimicking life. Such is the conquest of what might be the perception of “play” in Alÿs’s film. While a triumph in survival, it also somehow feels like the concept behind “Death 24x a Second”. The boys race against an invisible clock, running up a hill as passersby look on.

|

| Francis Alÿs (In collaboration with Julien Devaux and Ajmal Maiwandi) REEL-UNREEL, 2011 Single channel video projection, 19:28 min, color, sound Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London |

As viewers we run right along with them. We are the reel, we are the road. Everything close up occasionally blurs while the background remains hazy, yet vast. As an altitude is achieved we are given an expansive depth of field and a pronounced circumference to peer into as our stillness follows their movement, or our perception of their movement.

Inside the gallery, flat white yoga mats and round oblong pillows have been placed around for visitors to recline on. While in one sweeping moment, as in all work shown via projection, it is possible to lose oneself but also be aware of us versus them, those inside the screen in relationship to those outside the screen. REEL-UNREEL feels incredibly distant and oddly familiar within the newly refurbished room in the gallery and uncomfortable juxtaposed against the world shown on the screen. As the boys near their destination, one wonders if they will go flying off the cliff. A section of the celluloid grazes over a small fire in the road and separates the connection the boys share. One races ahead and lets his reel go flying over a rocky ledge. He falls outside of the camera’s view. The other boy appears and his reel also goes over the edge. It is shortly thereafter that text appears on the screen and mentions the Taliban and how they burned hundreds of reels of film. The hopeful message is that of the bootlegs, the copies, the concept of blank or fraudulent film. The celluloid acts as an impossible mirror. One that we can pick up, hold in our hands and maybe even see our likeness within the shiny tape reflection or in the representation of other figures frozen in tiny cells. There are moments of the uncanny,where we watch a film, a play thing, a place of discovery of entertainment and of war. A mirroring takes effect as we view the children who in one particular scene examine raw footage, trying to decipher and identify figures from the celluloid. It’s Caravaggio’s figure of the Narcissus discovering and admiring his own reflection in a pool, but here we are enticed, suctioned and inadvertently part of it all, even by laying back and observing.

|

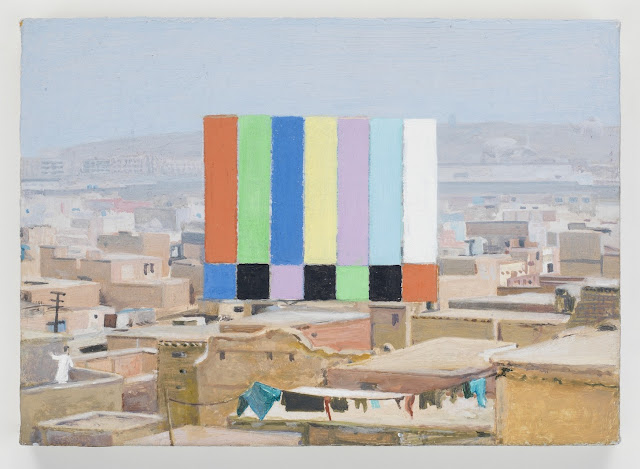

| Francis Alÿs, Untitled, 2011-2012, Oil encaustic on canvas on wood 5 x 7 inches (12.7 x 17.8 cm), Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London |

“This meeting of movement stilled and the still in movement coexist simultaneously within different time structures. In a dynamic or dialectical relationship, time is neither tied to the index and the past nor entirely freed from it; time is subordinate to the linearity of narrative movement and moves beyond and outside it.” ~Laura Mulvey, from “Death 24x a Second”, 2006

Alÿs has also included small paintings in the exhibition. Set apart from the large, single channel video are representational oil paintings with collage elements each featuring bold, graphic stripes, the kind found during a television station screen test. While in Afghanistan, working and editing the film, the artist noticed the bars often across t.v. screens. The bars became a meditative observation that Alÿs felt compelled to paint during his visits to Kabul, from 2010-2012. From the exhibition press release:

“Over those two years, the activity of obsessively painting color bars became an indispensable pendant to my travels in Afghanistan. Whether they reflect my difficulty to translate what I felt, or whether they simply became a therapeutic exercise at home in order to digest the flood of information received upon each visit, the viewer can decide.” ~ Francis Alÿs

|

| Francis Alÿs, Untitled, 2011-2012 Oil encaustic and collage on canvas on wood 4 7/8 x 6 7/8 inches (12.4 x 17.5 cm) Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

|

Rather than reflect our own experience and false memories into the paintings, Alÿs chooses to show an interpretation of his perception of visual interruption. The lyrical sketches of a world he was observing are not so unlike REEL-UNREEL however within the confines of painted surface. The opinion is just as forceful but somehow less challenging and not as emotionally available. But when bars appear across a television screen (at least in North America) they are usually followed by an extensive beep and the message “We are conducting a test of the emergency broadcasting system. This is only a test.”

And maybe that is true, this is only a test.

xo